Field Stories

Ten inspiring global nutrition stories

December 17, 2024

WP_Term Object

(

[term_id] => 49

[name] => Field Stories

[slug] => all-field-stories

[term_group] => 0

[term_taxonomy_id] => 49

[taxonomy] => news-category

[description] => Discover the personal stories of people whose lives have been impacted by better nutrition, and those working tirelessly to deliver it.

[parent] => 0

[count] => 180

[filter] => raw

)

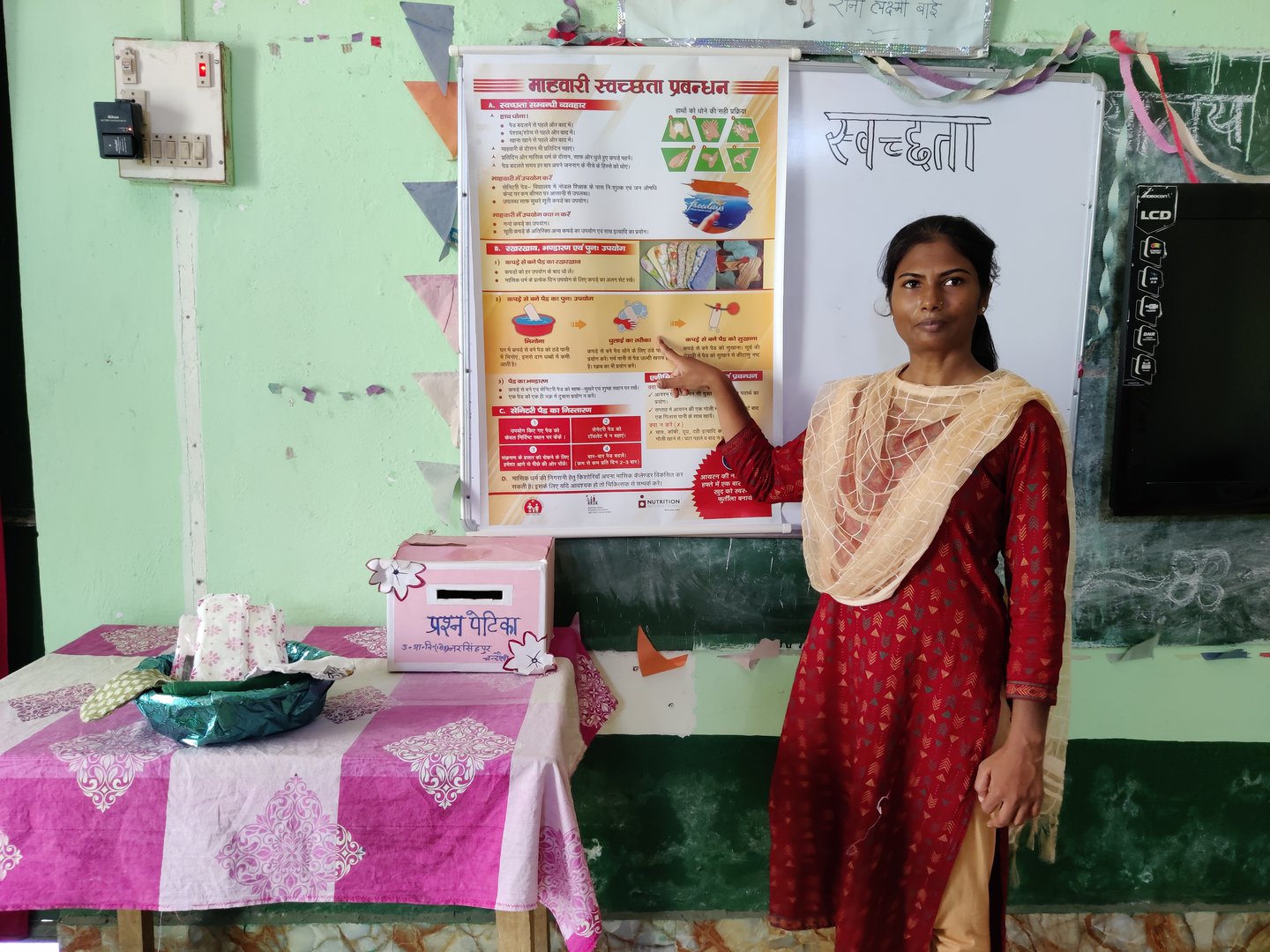

From period stigma to peer support

How a pilot initiative in Uttar Pradesh is helping adolescent girls take charge of their menstrual health.

Posted on August 31, 2022

Across Chandauli district, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, India, adolescent girls are speaking up about a subject once considered unmentionable – their periods. With support from a new initiative promoting menstrual health and hygiene, they’re working to challenge misconceptions and stigma that have been passed down through generations of women.

In the rural community of Baheri, we speak with 13-year-old Rubi, a keen eighth-grade student who lives with her parents and three siblings. Her father’s wages from construction labour, though inconsistent at times, manage to sustain the family and allow Rubi to pursue her education. But when her first period arrived it threatened to derail her plans for the future.

“When my family came to know about it, my mother instructed me to not take part in puja (ceremonial worship) and to avoid cooking, bathing and going outside our home,” she says.

“In the rural context, there are quite a lot of myths regarding hygiene during menstruation.

— Sangeeta Karmakar, State Program Representative

With little guidance beyond this list of restrictions, Rubi was forced to improvise. She made use of an old cloth, changing it only once per day and later disposing of it covertly in the fields or the jungle near her village.

According to India’s National Family Health Survey (2019-21), only 72.6% of adolescent girls and women aged 15 to 24 use hygienic methods of protection during their periods in Uttar Pradesh. That means more than a quarter in that age bracket do not. Although menstrual hygiene products are available in abundance in open markets, limited awareness of safe hygienic methods, hesitation among girls in conservative families to ask for money to buy products, and unaffordability continue to cause barriers to access.

Like many girls in her village, Rubi was initially afraid to confide in anyone about the new challenges her period caused her to navigate. But when she felt that she could no longer manage the situation alone, particularly when it prevented her from going to school, she summoned the courage to act. She went to her teacher, who had recently spoken about menstrual hygiene in the school, for help.

Moving menstrual hygiene into focus

In March 2020, Nutrition International launched a menstrual health and hygiene pilot initiative in Chandauli, building on its work with the state government to address adolescent anaemia through weekly iron and folic acid supplementation (WIFAS) and nutrition education.

“In the rural context, there are quite a lot of myths regarding hygiene during menstruation. That is something that came out in our activities on adolescent anaemia,” says Sangeeta Karmakar, Nutrition International’s state program representative. She explains that while the state government had a menstrual hygiene management program in place, it hadn’t been an area of focus until now.

The pilot project aimed to increase knowledge of menstrual hygiene practices among teachers and health workers, thus improving their capacity to support adolescent girls through this critical life stage. As a first step, Karmakar’s team worked with the state departments of health and education to develop training materials and establish selection criteria for trainers as well as participating teachers – one from every school in the district. Trainers were asked to take on a mentorship role and were required to have experience in the promotion of menstrual health and hygiene at a community level, while teachers needed to have an open mind and a degree of comfort in addressing the issue with students.

“They should be ready to counsel the students. If that willingness is there, then only we select the teacher,” says Karmakar.

Mentors were tasked with guiding teachers through the curriculum and demonstrating counselling techniques. They would also engage staff at anganwadis (community outreach centres), equipping them with the knowledge and skills to reach out-of-school adolescents. Once teachers and health workers were trained, they would be able to hold regular group counselling sessions with adolescent girls across Chandauli.

Adapting to the COVID-19 context

Emerging soon after the pilot’s launch, the COVID-19 pandemic presented sudden and significant operational challenges. With schools closed, the team looked for other ways of reaching their audience. Online counselling sessions could serve urban and wealthier populations, but the program was intended to target lower income groups who did not have the same level of access to digital technologies.Village health and nutrition days (VHNDs) were the one platform that continued to deliver services to rural communities throughout the pandemic. The team leveraged these monthly events to engage both school-going and out-of-school adolescent girls.

As VHNDs were held across Chandauli, mentors spent full days in each village, convening small groups of 15-20 girls at a time in an effort to maintain COVID-19 protocols. After a handful of sessions, they handed the reins over to teachers and anganwadi workers on the frontlines, providing supervision and support.

Although the rollout has been much slower than initially planned, the team has been energized by the response of the girls. “They were quite enthusiastic,” says Karmakar.

As the pandemic situation evolved and in-classroom learning resumed, teachers started holding regular counselling sessions in schools to reinforce the message and encourage the adoption of safe menstrual hygiene practices.

Bringing the lessons home

Through these sessions, Rubi learned that menstruation is a natural part of growth and development, and that proper hygiene and nutrition could help her stay in school during her period. She also learned that it was important to share the message with her family.

She carried the lessons home to her sister and mother, eventually shifting their mentality on the shame and misconceptions they had inherited. They began to use sanitary pads purchased from the government medical store, changing them three to four times a day and disposing of them safely in the pit they dug behind the house. When pads were either too costly or unavailable, they used clean and dry cotton cloth.

Having learned about the importance of nutritional diversity, Rubi also urged her mother to incorporate iron-rich leafy vegetables, pulses and beetroot in her cooking.

“I feel the knowledge I received from my teacher on menstrual hygiene empowered me and helped me to be aware and counsel my elder sister and mother

— Rubi, Grade 8 student, Uttar Pradesh, India

“I feel the knowledge I received from my teacher on menstrual hygiene empowered me and helped me to be aware and counsel my elder sister and mother,” says Rubi, who has quickly emerged as a champion for menstrual health, providing comfort and guidance to her peers. “I am always reachable to my friends when they seek information on menstruation.”

Ameet Babre, National Program Manager of Health Systems at Nutrition International, explains that while the pilot project grew out of Nutrition International’s work on adolescent anaemia, the broader goal is to improve the health and well-being of girls through a positive school environment. This includes access to information, available and affordable menstrual hygiene products, sanitation and washing facilities, safe disposal mechanisms for products, and an end to harmful myths and taboos.

“It’s not about the medical aspect of what is the relation between nutritional anaemia and menstrual hygiene,” says Babre. “It’s about empowering girls and showing them a more holistic approach that brings change.”

Extending the impact

While the impact of the pilot initiative has yet to be formally evaluated, testimonials like Rubi’s are encouraging. Field teams have also noted that teachers are not only embracing their counselling role but moving beyond it – digging pits on school grounds for product disposal and working with school management to ensure a regular supply of clean water. The team hopes the pilot will yield insight and learnings that will allow them to advocate for the integration of menstrual health and hygiene in adolescent nutrition programs across the state.

“It’s about empowering girls and showing them a more holistic approach that brings change.

— Ameet Babre, National Program Manager of Health Systems

For the moment, the pilot’s goal is to reach 70,000 adolescent girls in Chandauli, but Babre also highlights the importance of eventually engaging male students as well. “These are the adolescent boys who are going to get married tomorrow and will be running a family, so their sensitivity for this particular issue is important,” he says.

Plans are also underway to connect directly with a broader youth audience. Working alongside the state government, Nutrition International is creating series of short, animated videos that will demonstrate the benefits of menstrual hygiene management in a clear and compelling way. These videos might tell the stories of young women like Rubi, who in adopting a handful of simple practices, are able to comfortably manage their periods, stay focused on their studies, and encourage their friends to do the same.