Field Stories

WATCH: Women inspiring action, prioritizing good nutrition

March 6, 2024

WP_Term Object

(

[term_id] => 136

[name] => Blog Posts

[slug] => all-blog-posts

[term_group] => 0

[term_taxonomy_id] => 136

[taxonomy] => news-category

[description] => See what’s top of mind for our technical experts as they share the latest on cutting-edge nutrition research, policy updates, and implementation guidance.

[parent] => 2025

[count] => 137

[filter] => raw

)

What do people actually think about gender? Perspectives from the field

Nutrition International’s Senior Gender Equality Specialist reflects on candid conversations she’s had in different countries when it comes to gender barriers and nutrition.

Posted on March 1, 2024

Meeting with healthcare workers and community members at a posyandu (integrated service post) in Cikadu, West Java, Indonesia.

Since the lifting of COVID travel restrictions, I’ve been able to visit a number of our country offices, providing face to face training workshops on gender equality. I’ve engaged in many meaningful conversations around what it means to promote gender equality within nutrition programs. After two-plus years of COVID lockdowns it has never felt more important to engage with people in person on topics that can feel complex and difficult to navigate through online webinars across time zones.

One of the things I noticed when holding training sessions on gender equality or discussing it in informal conversation is that people can have very strong reactions: usually it swings between excitement and enthusiasm to learn more and gain skills to nervousness, or uncertainty. This is often because of a lack of understanding coupled with mixed messages that may be out in the media. In many ways I feel that my role as a gender specialist is to listen carefully to what people are saying and then begin a process of asking questions, presenting scenarios, and encouraging dialogue. I want to help demystify what it means to promote equality and empowerment within the context of our nutrition programs.

Often, people want to know what our “position” is on something related to gender. I try to reframe that as I don’t think it is the most useful question to be asking. If we make gender an issue where we must adopt a position, it makes it harder to actually address the real problems. It shifts the focus onto an abstract ideal, not the real thing staring us in the face. It’s girls in India who feel more confident when they have their period to still attend school and their male classmates no longer tease them. I think about the fathers I met in Tanzania who laughed during a focus group when asked if they also spend time looking after their babies or if it is only the mother. They readily spoke about how times have changed from when they were children – an important reminder that gender norms and roles are not static.

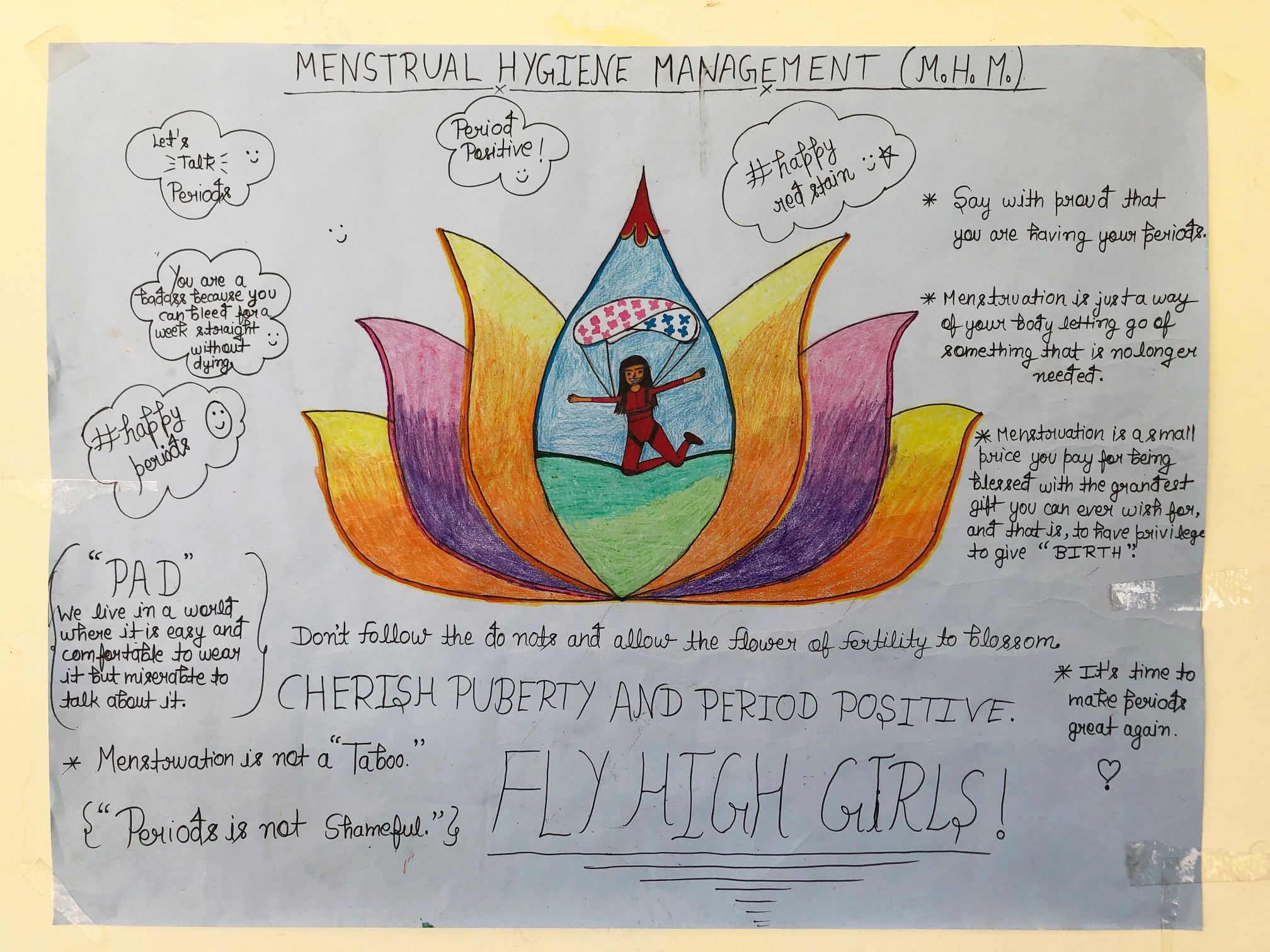

We work across many cultures, and it is true we need to be mindful that what might be safe and acceptable to talk about in one place may not be the same in another. This is why it is important to partner with local women’s rights organizations, as they are already championing for gender equality within their own cultural context. I have noticed signs all over the world clearly highlighting the fact that gender equality is on the minds of those from all cultures.

Coming back to Delhi after a field visit from another part of India, I noted the domestic airline was promoting girls’ empowerment with the tagline, “30,000 feet above the patriarchy.” In Indonesia, during a learning forum with government partners, there were many discussing how they might make their nutrition programs more gender sensitive. I’ve also found that you only need to ask male colleagues what kind of future they hope for their daughters to realize that this desire for equality is nascent within each of us; but it requires getting personal and making ourselves vulnerable. At the end of the day, it comes down to treating all people with inherent dignity and respect, both at an individual and at a systems level, and recognizing that for some it is not always readily given.

“At the end of the day, it comes down to treating all people with inherent dignity and respect, both at an individual and at a systems level, and recognizing that for some it is not always readily given.

One of the exciting initiatives I have been working on recently is a process to refresh and update our program gender equality strategy, which will be released later this year. This has involved many months of consultation where I’ve sat in focus group discussions and listened to our staff reflect on their experiences of learning about and working on integrating gender within our programs. Some of their comments have stayed with me. For example, a colleague in Ethiopia said, “Without addressing core issue of gender, [such as] decision making power and access to resources and power at household level we may not make much progress towards improving nutrition.” To me this demonstrates an awareness that he does not see gender as an add-on or tick-box exercise but that it is intrinsically linked to our work.

Another colleague from India said, “It’s about what people actually think and their attitudes and beliefs around equality and those dynamics in the household that make it challenging for women to have good nutrition.” For me this is critical, and it begs the question, what is informing how people think? Furthermore, what is preventing people from seeing how their beliefs about gender equality affect the well-being of women and adolescent girls?

We’re all a product of our upbringings and live with unconscious biases, which are the brain’s natural way of navigating and organizing the complexity of information we are bombarded with on a daily basis. However, these biases can create barriers so it’s important to be aware of our underlying assumptions and beliefs. Our training session on unconscious bias has built in spaces for staff to reflect together on their own experiences of gender, which helps to make connections with how gender norms and roles influence our programs.

As I think about the theme of this year’s International Women’s Day, #InspireInclusion, it has never felt more appropriate. The above only highlights a few of the examples of how Nutrition International supports this in our programs – and there is still so much more work to be done. Part of that work is to continue these conversations and have honest dialogue. This is essential if we want to build effective partnerships and support efforts that will reduce barriers for all women.